What is Ecological Restoration?

According to the Society of Ecological Restoration (SER), ecological restoration sensu stricto is defined as “the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed” 1. This means that ecological restoration aims for the highest level of restoration possible based on a reference ecosystem or a reference model. This therefore takes into account extreme disturbances and climate change. The ultimate goal is to restore the ecosystem’s capacity to function and evolve naturally, as if it had never been disturbed, following a known recovery trajectory or adapting to global change.

Beyond merely mitigating damage, ecological restoration actively supports, accelerates, and guides the regeneration of ecosystems, ensuring that they regain their resilience and autonomy. A fully restored ecosystem should be able to sustain itself without ongoing human intervention, relying on its natural self-regenerative processes.

The Restorative Continuum

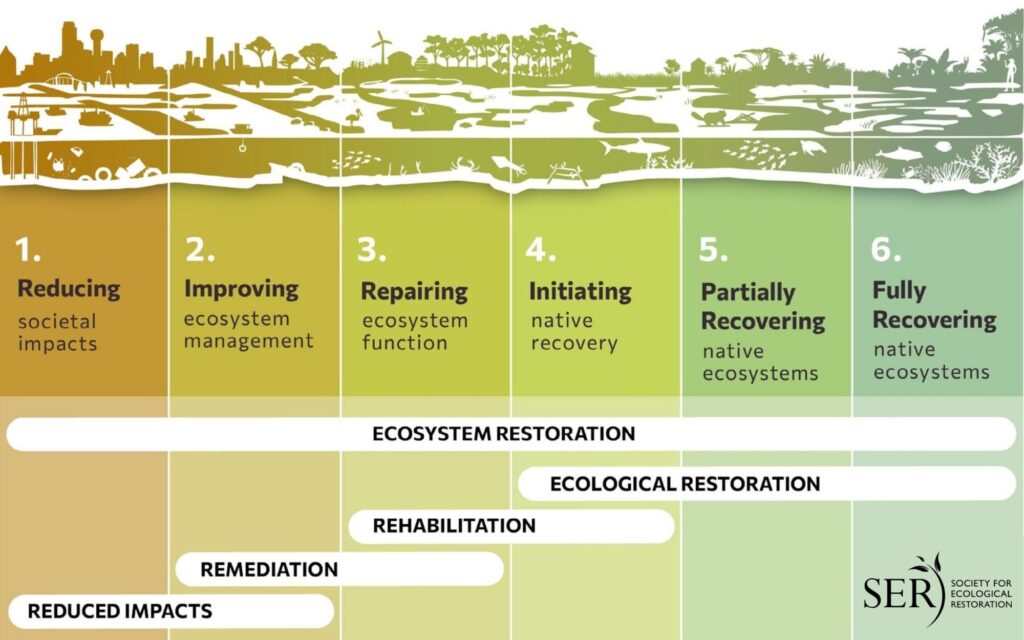

However, while the above mentioned definition is precise, it is also quite restrictive. In practice, restorative activities span a broader restorative continuum, ranging from reducing the drivers of degradation to achieving full ecological recovery. This continuum2 acknowledges that restoration efforts can vary in intensity and scope, integrating complementary actions that can be implemented simultaneously or sequentially. Such an approach allows for the scaling up of restoration efforts to larger spatial scales, maximizing ecological benefits and enhancing ecosystem resilience 3.

Marine restoration occurs in marine systems, including but not limited to, coastal areas, the open ocean, and the deep sea.

For a comprehensive introduction to marine restoration, listen to the episode "What is marine restoration?" in SER Europe's series Resilient Seas.

Scaling in Ecosystem Restoration

As marine restoration is a growing field, it is important to disseminate learning and practices to scale effective solutions across geographies, communities, and governance systems. This assists in the broader uptake of restoration approaches and improves cost-efficiency of current and future restoration. However, scaling is not a linear process as it is shaped by complex dynamics not only on ecological baselines, but also political priorities, financing mechanisms, and levels of community engagement.

Three complementary approaches to scaling can guide this process: scaling out, scaling up, and scaling deep 4, 5.Each approach targets different levels of change and requires tailored strategies to ensure economic, ecological, and social viability.

While these strategies offer complementary pathways, their effectiveness depends on a deep understanding of local contexts and careful attention to potential risks, such as rapid or unadapted scaling, overlooking cultural differences, or lacking the necessary support structures. Scaling must be grounded in local realities, including financial and regulatory constraints. Monitoring, evaluation, and participatory learning are essential to ensure scaling efforts remain adaptive, inclusive, and impactful over time.

Benefits of Ecological Restoration

The overarching goal of marine restoration remains consistent: to identify and implement solutions that are both successful and beneficial. These two terms, however, are frequently conflated.

SER Definition of "Success"

Restoration that enables the recovery of biodiversity and ecosystem functions or services of a degraded ecosystem to levels not significantly different from those observed in appropriate reference sites, characterized by relatively intact, pre-disturbance conditions

- Positives

- Rigorous definition

- Negatives

- Often too restrictive

- Exp: Actions such as mitigation, remediation, or rehabilitation may not achieve full restoration sensu stricto but can yield meaningful ecological outcomes by moving systems toward improved conditions

- Positives

Common language definition of "success"

When a project achieves its stated objectives

Solutions

It is essential to complement compliance-based evaluations with assessments of the ecological benefits of restoration. Here, we refer to ecological benefits as the positive outcomes and impacts resulting from restoration efforts such as the recovery of biodiversity, habitat creation, carbon sequestration, or the enhancement of nutrient cycling. This notion aligns with the concept of “functional success” 10, which emphasizes the recovery of ecosystem processes and services rather than mere compliance with initial objectives.

The idea of quantifying restoration success through functional indicators is not new; it originates from regulatory frameworks that require compensatory replacement of ecosystem services lost due to environmental damage 12 . However, applying this approach to ecological restoration projects remains challenging. Most current efforts are still conducted at pilot or experimental scales 13, and measuring ecological benefits is often constrained by limited spatial or temporal coverage. Moreover, monitoring programs are frequently short-term due to financial or logistical constraints, even though ecological recovery can take years or decades to become measurable. Finally, in many cases, standardized and robust tools to evaluate ecological benefits are still lacking.

A shift toward assessing functional ratherr than solely compliance-based success is therefore crucial to better understand the true ecological value of restoration interventions and to guide future investments toward genuinely sustainable outcomes.